Material research

Material is very important in Emi’s work. Since she began working with textiles, she has naturally chosen to use only natural materials, something that may be connected to her background. Her first research focus was silk, and she discovered that silk takes natural dyes beautifully. She continued her research in Japan, studying silk production, metal yarns, and fibres made from plants and bark.

Emi deeply respects traditional textiles and techniques, and they continue to inspire her practice. Since she entered the world of textiles, the journey has felt endless, as there are so many traditional methods and textile cultures around the world to learn from.

Japanese silk and kibiso silk

Emi has researched Japanese silk yarn from the silkworm farm all the way to the spinning mill. Through her natural dyeing research, she discovered that silk produces the richest and most beautiful colours, which led her to learn more deeply about how silk is made. In Japan, creating a product such as a kimono involves many different craftsmen—farmers, spinners, dyers, weavers, and sewers—each specialising in one stage of the process.

To understand silk yarn properly, Emi visited a silkworm farm, a mawata fleece studio, and a family‑run silk spinning mill. Mawata is like a silk fleece: the master stretches the cocoon into a small square about 20 cm wide, and then two masters stretch it further into the size of a futon duvet. These layers are then built up to create futon padding or warm clothing.

At the spinning mill, the family carefully checks each cocoon by hand before placing it into the spinning machine, because the silk fibre is extremely fine and needs delicate handling. It was here that Emi discovered kibiso yarn, which later became one of her favourite materials. Kibiso is very textured and uneven in thickness. It comes from the outer layer of the cocoon, which is hard and unsuitable for making fine silk yarn. Traditionally, this part was thrown away or used to make paper.

Although kibiso is stiff at first, it softens beautifully over time. Emi loved both the texture and the story behind it. Since then, the owner of the mill has been saving the kibiso yarn for her and sending it to her for her work.

Emi is inspired by Andean textiles made from alpaca, llama, and vicuña wool. Their traditional weavings often feature diamond patterns and are coloured with natural dyes sourced locally. Wanting to understand this connection between animals and textiles more deeply, she spent time at Toft Alpaca Farm in England.

There, she learned hand‑spinning, hand‑knitting, and felting, and she also had the opportunity to visit the weaving mill. She experienced everything from caring for the alpacas to harvesting their fibre, giving her a full understanding of the process from animal to textile.

Alpaca yarn

Copper yarn

Emi has researched how to create a turquoise colour using natural dyeing.

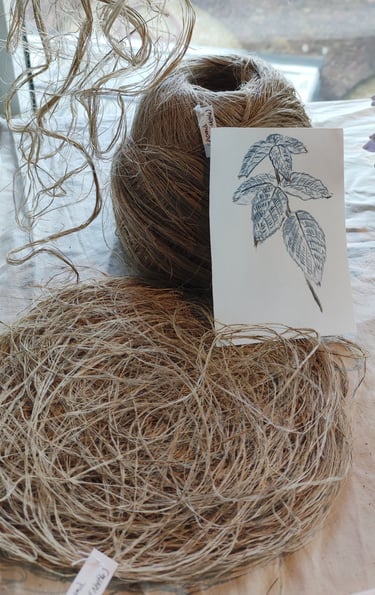

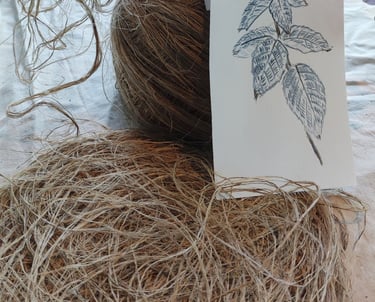

flax yarn

Linen has long been a central textile in Eastern Europe, and Emi’s connection to it began with a deep curiosity about the region’s traditions. In 2012, she had the opportunity to take part in a placement in Romania, where she immersed herself in traditional farm life—from food culture to textile practices. Years earlier in Japan, she had read an article explaining how villages across Transylvania—both Romanian and Hungarian—each have their own distinctive embroidery styles, symbols that represent the identity of their communities. That idea stayed with her.

Her journey continued through several visits to Slovenia, where she collaborated with flax weavers and national projects. Alongside this, she developed a passion for collecting antique and vintage Eastern European linen textiles, which naturally deepened her desire to understand the full process of transforming flax into linen fabric.

This led her to a flax field in the Cotswolds, where she learned the traditional methods of processing flax plants into fiber. Inspired by this experience, Emi went on to establish her own “seed‑to‑textile” flax projects in two different communities in England. One of these projects became part of her art in residency and was later displayed at the Contemporary Art Northampton.

Wisteria Bark Yarn, Nettle Fibres, and Japan’s Bast‑Fibre Traditions

Bark yarn — especially from plants in the nettle family — has been part of Japan’s textile heritage for centuries. Many regions developed their own sustainable and ethical techniques, shaped by the plants available in their landscapes. One important material was bast fibre, the strong inner fibre found inside the bark. In Japan, this was often taken from wild nettles known as chōma, which could be gathered even from roadsides near the fields and mountain paths.

Emi’s work centres on fuji weaving, a rare tradition that uses bast fibres extracted from wisteria bark. Wisteria has always been meaningful to her — it is one of her favourite plants, and her surname is also connected to wisteria — so the material immediately captured her attention.

A particular form of bark‑fibre weaving called tafu developed in only a few regions of Japan. Emi was introduced to this tradition by Kei‑san, an antique textile collector and owner of Gallery Kei in Kyoto. Kei‑san taught her about the history, techniques, and cultural significance of tafu weaving, opening a path into a craft that is both beautiful and deeply rooted in hardship.

The process of making wisteria bast fibre is extremely demanding. Historically, farmers had little choice: winter offered few ways to earn money, so extracting and preparing these fibres became a necessary part of survival. The yarn is stunning, but it carries a difficult past — much like boro textiles, it reflects the resilience and struggle of rural life.

Years later, Emi had the rare opportunity to participate in the creation of wisteria yarn in Japan. Since then, she has continued experimenting with the process from her base in England, bridging traditional Japanese knowledge with her own contemporary practice.